What keeps pulling me back into Stone Age archaeology is not the drama of survival, but the precision of it. The longer I work with healer-women stories and the material record that underlies them, the more I find myself stopping over questions that sound almost trivial—until you realize how much depended on them.

Why build a fire here and not ten meters away?

Why keep returning to spots that offer no shelter at all?

Why do some places show intense use for centuries, then vanish entirely?

And why, so often, was “good enough” better than “perfect”?

These questions are not abstract. They sit at the heart of how people survived without maps, property, or infrastructure—how they learned which places worked, which failed, and which were worth testing again. What fascinates me most is that Stone Age people did not treat land as neutral. They treated it as something with behavior—something that could be learned, remembered, and misjudged.

This post is about those choices. Not where people lived in a general sense, but where they did things—and why those places mattered.

The moment

The fire doesn’t work.

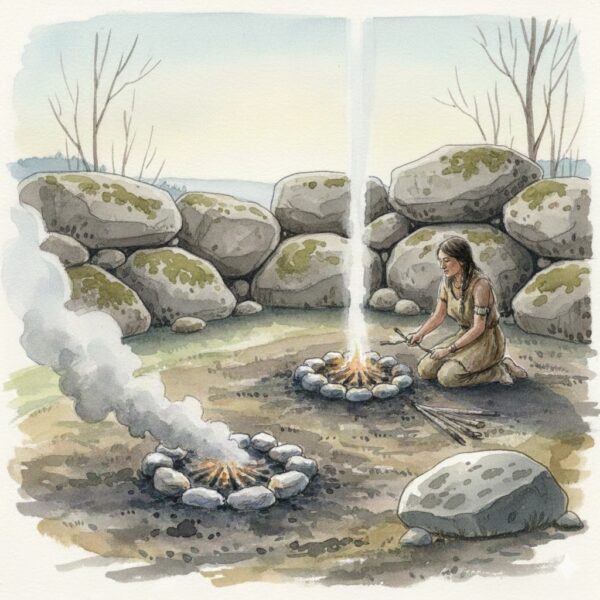

Smoke pools low and heavy, clinging instead of lifting. Her eyes sting. The heat escapes sideways instead of holding. She shifts the fuel, then stops. The problem isn’t the fire. It’s the place.

She moves the work a short distance downslope, where the ground is firmer and the air moves differently. The second fire draws cleanly. Smoke lifts. Heat settles. No one announces the change. No one explains it. The place has been tested, and it has failed.

This is the moment archaeology rarely shows directly—but it leaves traces everywhere. Places are not chosen once. They are corrected. Adjusted. Abandoned. Remembered.

Stone Age people did not arrive in a landscape already knowing where to stand. They learned it by doing—and by noticing when something went wrong.

The core idea — places were tools

The idea that anchors this entire post is simple, and easily missed:

In the Stone Age, places were tools.

They were selected, tested, maintained, and discarded just like tools. A place that worked reduced effort and risk. A place that failed demanded more labor—or caused harm. This is why people returned to certain locations even when those locations offered no obvious shelter or resources. They returned because those places had proven reliable in specific ways.

This is not about sacred sites or symbolic landscapes. It is about function.

Fire places — where flame behaves

Fire is the clearest example of why place matters.

Across much of Europe and western Asia, archaeological sites dated roughly 200,000 BCE to 12,000 BCE show repeated hearth construction in nearly identical locations. Ash layers stack vertically. Burnt earth compacts. Stone debris clusters in familiar arcs around the fire.

What this tells us is not simply that people used fire—but that they remembered where fire worked.

Fire behaves differently depending on: slope, ceiling height, airflow, ground composition, proximity to moisture.

A fire placed too close to a wall smokes. One placed too low floods. One placed too high loses heat. Moving a fire even a meter can change its behavior completely.

One of the more surprising findings from cave and rock-shelter sites is that hearths are sometimes placed away from the most sheltered areas. Why? Because draft matters more than cover. Smoke blindness is not a minor inconvenience—it is dangerous.

People returned to hearth locations not because they were comfortable, but because they were predictable.

Butchery places — where mess belongs elsewhere

Another category of place use becomes visible once you stop assuming that camps were all-purpose “homes.”

Large animals were rarely processed where people slept. Across Upper Paleolithic sites dated roughly 40,000–12,000 BCE, archaeologists see dense bone concentrations, cut marks, and marrow extraction debris located downhill, downwind, or at the edges of occupation zones.

These are work places, not living places.

Butchery creates blood, waste, insects, and smell. Keeping it separate reduces disease and scavenger attraction. It also allows multiple people to work without disrupting the rest of the camp.

One of the more counter-intuitive insights from the archaeological record is that many sites show intense activity without long-term habitation. These places were never meant to be lived in. They were used for specific tasks and then left behind.

In other words: Stone Age people did not live everywhere they worked.

Healing and care places — where movement slows

Care and healing introduce another kind of place use—one defined not by productivity, but by limitation.

Skeletal remains from Paleolithic contexts frequently show healed fractures, joint degeneration, and tooth loss followed by continued survival. Healing takes weeks or months. During that time, movement patterns change.

Places associated with care tend to show: longer occupation spans, repeated hearth maintenance, easy access to water and fuel, fewer signs of large-game processing.

The safest place was not always the most sheltered. It was the place easiest to keep warm, fed, and clean. These were not heroic spaces. They were practical ones.

Choosing where an injured person stayed was a decision with long-term consequences. A bad location increased labor for everyone. A good one made survival possible.

Tool work and repair — where attention matters

Stone tools are often imagined as objects of creation—moments of invention frozen in time. Archaeology tells a different story.

From around 70,000 BCE onward, stone tools show extensive evidence of maintenance. Retouch flakes cluster near hearths rather than at kill sites, indicating that sharpening and repair happened in camp, before work began.

Tool repair requires: stable seating, good light, predictable surfaces, time

These are not dramatic places. They are quiet ones. Many sites are surrounded by thousands of tiny flakes—the byproduct of upkeep, not innovation.

This tells us something important: Skill was not concentrated in moments of making, but in routines of care.

How archaeologists know — reading places, not stories

Archaeologists do not identify places of use by intuition. They do it through pattern.

Archaeologists look at: spatial clustering (what happens where), repetition across layers (what returns), wear patterns on ground and objects, absence (what does not appear in a place).

A hearth area looks different from a butchery area. A repair space leaves a different signature than a sleeping space. These signatures repeat across regions and time periods, which is why they can be interpreted with confidence.

Places, like tools, leave fingerprints.

Why “good enough” often beat “perfect”

One of the most modern mistakes we make when imagining the past is assuming people always sought the best possible location.

They didn’t.

They sought places that were known.

A slightly exposed spot that behaved predictably was often better than a perfectly sheltered one that hadn’t been tested. New places carried unknown risks. Known places carried measured ones.

This is why people returned to valleys even after bad years. Not because they believed things would improve, but because returning was the only way to find out whether the place still worked.

Women and place-knowledge

Much of the fine-grained knowledge archaeology reveals—where smoke lifts, where bodies heal best, where tools are repaired efficiently—comes from repeated daily tasks.

This kind of knowledge accumulates through attention and repetition, not through authority or strength. It is not flashy. It does not announce itself. But it structures survival.

In the healer-women stories I write, this is what draws me in: not the drama of care, but the intelligence embedded in choosing the right place to do it.

What remains

Stone Age people did not live everywhere. They lived where things worked.

They tested places. They corrected mistakes. They remembered outcomes. And when a place failed repeatedly, they let it go.

What remains in the archaeological record is not just evidence of where people were—but evidence of where they chose to be, again and again, because the land had answered them before.

That, more than any monument or myth, is how deep time remembers.