I keep returning to the knowledge that shaped human life long before farming, writing, or certainty. This post begins with a small imagined moment—a woman gathering plants at the edge of a spring valley—and then turns to the archaeological record that lets us glimpse what plant knowledge meant for early Homo sapiens in the Stone Age.

Drawing on evidence from Ice Age Europe, I explore prehistoric foraging, ancient plant medicine, fibers, and seasonal rhythms not as background details, but as the structure of daily survival. Long before farming, people relied on plant knowledge so precise that archaeologists can still detect seasonal harvesting patterns tens of thousands of years later.

This is the world I am trying to recover in my writing: one held together by women’s knowledge of ancient flora—food, healing, fuel, and materials—where continuity mattered more than spectacle, and where living meant paying attention, remembering, and enduring uncertainty.

The moment

The basket was already half full, though the sun had not yet cleared the ridge.

She moved slowly along the damp edge of the valley, where meltwater lingered longest. Last year’s stems still stood in places, gray and brittle, but at their base new growth had pushed through. She did not pull everything she saw. Some plants were left untouched. Some were taken carefully, roots loosened and wrapped. Others were only marked in memory.

There was no hurry. The animals would not arrive for weeks yet, if they came at all. But plants came earlier. They always had.

By the time she returned to the camp, the fire was awake. The basket was set down. Nothing was announced. What mattered would be known later — in the taste of food, in the easing of a cough, in the way a wound closed instead of darkening.

Foundational archaeological perspective

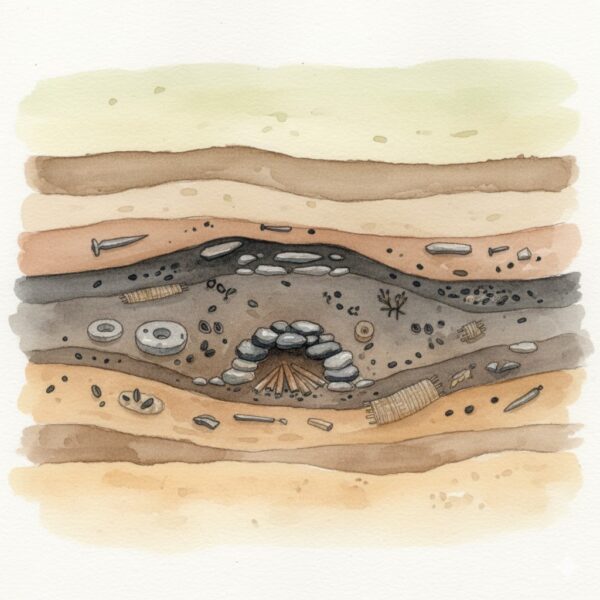

Plants rarely survive in the archaeological record. This is the first and most misleading fact about ancient flora.

Unlike bone or stone, plants decay quickly. Leaves rot. Stems collapse. Roots vanish. What survives does so unevenly — charred fragments in hearths, microscopic pollen trapped in sediments, phytoliths embedded in dental calculus, fibers preserved in rare anaerobic conditions. As a result, plant use has long been treated as secondary, invisible, or supplementary.

But invisibility in preservation does not equal insignificance in life.

Across Paleolithic and Middle Paleolithic sites in Europe and western Asia — including Neanderthal contexts — plant remains appear consistently when conditions allow their survival. Charred seeds appear in hearths. Starch grains adhere to stone tools. Pollen spectra shift in occupation layers in ways that cannot be explained by wind alone. Dental calculus preserves traces of cooked and uncooked plants, medicinal species, and fibers not eaten at all.

These traces are fragmentary, but they are widespread. And they point to something clear: plants were not occasional supplements. They were a constant presence.

Reading risk in the archaeological record

Plant use rarely announces itself dramatically. There are no mass kill sites for tubers. No bone piles to signal abundance or collapse. Instead, risk is read differently.

One signal is seasonal breadth. At many sites, plant remains indicate use across multiple seasons, including times when large game was scarce or absent. This suggests plants were not fallback foods chosen in desperation, but predictable resources integrated into annual cycles.

Another signal is diversity. Archaeological plant assemblages, where preserved, often include multiple species with different properties: caloric roots, bitter leaves, aromatic plants, fibrous stems. Diversity is not random. It reflects knowledge — of location, timing, processing, and effect.

A third signal is processing effort. Some plant foods require soaking, grinding, roasting, or repeated leaching to remove toxins. These steps leave subtle traces: grinding stones with starch residues, hearths with repeated low-temperature burning, spatial clustering of tools associated with preparation rather than consumption.

Risk appears not in the presence of plants, but in how intensively they are processed. When plant use shifts toward bitter, fibrous, or low-calorie species — and when processing becomes more laborious — it often coincides with periods of environmental instability or faunal unpredictability.

In other words, the archaeological record shows plants absorbing risk that animals could not.

How do we know this happened?

Archaeologists do not infer plant knowledge from a single line of evidence. They reconstruct it by layering weak signals until they align.

Dental calculus preserves microscopic plant remains lodged between teeth during life. These include starch grains from roots and seeds, phytoliths from leaves and stems, and residues from medicinal plants not eaten for calories. In Neanderthal individuals, calculus has revealed cooked starches, bitter compounds, and plants with known antimicrobial properties.

Use-wear and residue analysis on stone tools identifies plant processing even when no macroscopic remains survive. Microscopic polish, striations, and embedded residues distinguish cutting stems from scraping hides or slicing meat.

Charred plant remains appear in hearths when food preparation overlaps with fire use. Their presence implies deliberate cooking or drying, not accidental burning. Some species appear repeatedly, suggesting preference and planning rather than opportunistic gathering.

Pollen and phytolith assemblages in occupation layers differ from surrounding sediments. This indicates plants were brought into sites intentionally, not simply tracked in by wind or animals.

Individually, each line of evidence is fragile. Together, they are decisive.

Plants were known. Plants were used. Plants were managed in time, if not domesticated.

Living inside uncertainty

Plants occupy a different temporal logic than animals.

Animals arrive and depart. Plants emerge, mature, and vanish on predictable schedules — but those schedules shift subtly with snowpack, rainfall, temperature, and soil disturbance. A late frost delays shoots. A dry spring reduces yields. A flood erases access routes.

Living with plants requires attention rather than pursuit.

The archaeological record reflects this in small ways. Gathering tools appear alongside hunting tools, not after them. Plant residues appear in camps occupied year-round, not only during periods of faunal abundance. Processing areas persist even when animal remains thin out.

Plants did not replace animals. They stabilized life around them.

This stabilization had social consequences. Knowledge of plants accumulates slowly. It is not acquired through a single event, but through repeated observation across years. Children learn it by accompanying adults. Elders retain it because memory matters. Mistakes carry consequences that may not appear immediately — illness days later, wounds that fail to close, hunger that lingers quietly.

In this context, plant knowledge is not background. It is infrastructure.

What this meant in those times

Before agriculture, plants did not represent control. They represented relationship.

People did not sow or harvest fields. They returned to places. They watched. They remembered. They adjusted. Certain patches were used lightly. Others heavily. Some were avoided at specific times. Some were revisited year after year.

This behavior leaves almost no visible trace — and yet it structures daily life.

Long before farming, long before written knowledge, plant gathering formed the unseen foundation of daily life — especially for women responsible for food, healing, and continuity.

Plants provided:

- Calories when animals were absent

- Fiber for binding, baskets, and clothing

- Medicinal compounds that altered pain, infection, and inflammation

- Fuel, bedding, and insulation

- Predictable rhythms when other resources failed

Most importantly, plants allowed survival without spectacle.

There is no archaeological marker for the meal that prevented starvation but left no bones. No monument to the poultice that stopped infection. No stratigraphic signal for the fiber that held a tool together long enough to matter.

But absence itself becomes evidence. Sites persist through periods of faunal scarcity. Populations survive climatic swings that would otherwise be catastrophic. Injuries heal. Occupations continue.

Plants made that possible.

Closing note

Ancient flora rarely appears at the center of stories about deep time. It is quiet. It is dispersed. It resists simple narratives of triumph or collapse.

But that is precisely why it mattered.

Plants demanded patience, memory, and restraint. They rewarded attention rather than force. They shaped lives not through moments of abundance, but through continuity.

Long before fields, long before farming, long before certainty, people lived among plants and learned to read them — not as resources to be mastered, but as signals to be understood.

That knowledge did not announce itself.

It endured.