In Stone Age Europe, moments of uncertainty did not affect everyone equally.

For women in hunter-gatherer societies—those responsible for food processing, fat storage, tool preparation, childcare, and the continuity of knowledge—the failure of a seasonal expectation could reshape daily life for months. At many Ice Age sites, some large animals appear only in narrow seasonal layers, showing that people waited months—or years—for resources that might arrive for just a few days.

This post explores one such moment through archaeology-grounded storytelling: a time when waiting became dangerous, prediction failed, and the consequences of that failure were carried quietly through women’s work, memory, and survival before agriculture.

The moment

The tools were ready long before they were needed.

Edges sharpened thin enough to shave bark. Handles tightened. Old bindings replaced though they still held. This was done while frost still lingered in the shaded ground — done because last year the animal had come early.

It did not come early this time.

The elders waited. Fires stayed small. No one said it aloud, but everyone noticed the work already spent. By the third morning, people stopped walking to the river bend to look.

When the animal finally arrived, it was fewer than expected.

When it was gone, the work did not feel finished — only expensive.

Reading risk in the archaeological record

The scene above is fictional — but it is built from very specific archaeological patterns observed across prehistoric Europe.

This post focuses on Upper Paleolithic and early Holocene hunter-gatherers, roughly 45,000 to 8,000 years ago – spanning the final Ice Age and its unstable aftermath — in river valleys, floodplains, and meadow–forest edges. That sounds vast, but the subsistence patterns described here repeat with remarkable consistency.

The familiar idea that prehistoric people “waited for herds” is true — but it is not the important part.

What archaeology reveals, again and again, is something more fragile and more human: people built survival systems around predictions that could fail. Archaeology records absence as carefully as it records abundance.

How do we know this happened?

How do we know these animals were taken only at certain times?

Archaeologists do not infer seasonal hunting patterns by assumption or analogy. They reconstruct them using multiple independent lines of evidence that converge on the same conclusion. One of the most important indicators is tooth eruption and wear. By examining the developmental stage of teeth, researchers can determine the age of animals at death, and when this data is aggregated across a site, it often clusters tightly around specific months of the year rather than spreading evenly across seasons.

In the case of deer, antler growth provides an additional seasonal marker. Antlers recovered in early growth stages or still in velvet indicate spring or early summer kills. These biological clocks are difficult to misread and become especially powerful when combined with other data.

Seasonal isotopes preserved in tooth enamel add another layer of resolution. These isotopic signatures reflect diets tied to fresh spring vegetation, allowing researchers to distinguish animals killed during periods of new growth from those taken later in the year. Mortality profiles reinforce the pattern further. When animals are repeatedly killed in the same life stage, year after year, it indicates a targeted and predictable hunting window rather than random encounter.

When these signals line up, the conclusion is difficult to avoid: people were present in these valleys year-round, but these animals were not.

Why don’t these animals appear the rest of the year?

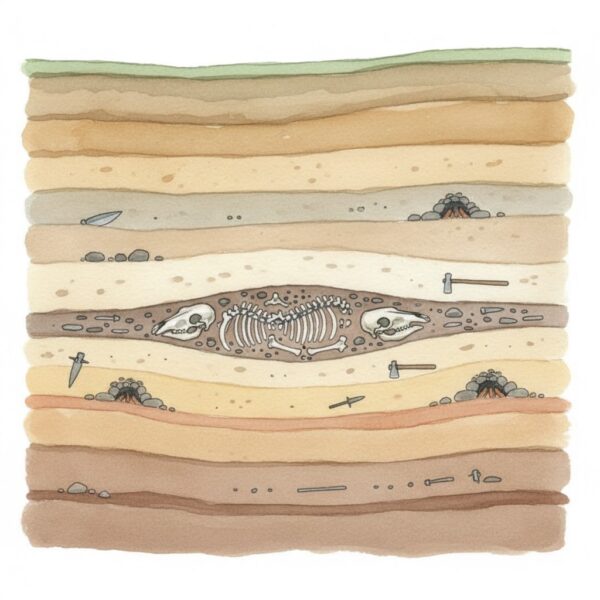

If people had access to large mammals such as red deer, wild horses, or aurochs throughout the year, their remains would be scattered across occupation layers. Instead, the archaeological record shows something very different. Bones from these animals often appear in dense clusters confined to narrow stratigraphic bands. Above and below those bands, the same species vanish entirely, sometimes for long stretches, even while evidence of continued human occupation accumulates.

This pattern matters because it rules out chance or preservation bias. Other animals continue to appear. Tools continue to be made and discarded. Hearths continue to be used. The absence is specific, repeated, and structured. It tells us the animals were not overlooked — they simply were not there.

Preparation before arrival is visible

One of the most overlooked findings in seasonal hunting archaeology is evidence for anticipation. At sites associated with spring hunting, archaeologists often find heavy cutting tools that show fresh retouch immediately before kill layers, suggesting sharpening and repair in advance of use rather than as a response to wear. Large hide-processing tools appear suddenly in the record, only to disappear again once the season passes.

Camps themselves sometimes show subtle reorganization consistent with the need to process very large bodies — changes in activity areas, refuse patterns, or tool distribution that do not persist into other seasons. Taken together, these signals indicate that people prepared in advance, sometimes weeks earlier, not in response to opportunity, but in expectation.

Waiting was not passive; it was a form of labor that could succeed or fail.

Waiting leaves traces.

Eating was immediate — but not all of it

Evidence from butchery marks and bone processing reveals a consistent pattern. Some meat was eaten immediately, often at or near the kill site, while the body was still warm. Fat-rich tissues were handled with particular care, because fat was critical rather than incidental. Marrow extraction was systematic rather than opportunistic, and bones were often broken in ways that maximized caloric return.

At the same time, drying and transport were clearly part of the strategy. Meat was moved and preserved while temperatures were still cool enough to slow spoilage. This was not a feast in the modern sense, but it was a moment of abundance following scarcity, and the social consequences of that shift would have been significant.

How do we see “bad years”?

The archaeological record does not preserve emotions, but it preserves stress. In some years, layers show fewer large animals taken, paired with more intensive bone breakage and higher rates of fat extraction. There is less selectivity in which bones are processed, and more evidence of labor-intensive strategies aimed at extracting diminishing returns.

In plain terms, people worked harder to get less.

These patterns appear repeatedly during periods of climatic instability toward the end of the Ice Age, when snowpack, grazing conditions, and migration routes became unreliable. What changes in the record is not just what people hunted, but how intensively they processed what they managed to obtain.

Why this mattered

For many hunter-gatherers, the most important animals were not part of daily life. They were anticipated for months, encountered briefly, and remembered all year. Children might see them once annually, or miss them entirely in a bad year. Knowledge, patience, and memory mattered as much as skill. For women, knowledge meant remembering patterns that no longer held.

This is the quiet reality behind seasonal hunting: not abundance, but dependence on prediction — and the consequences when prediction failed. In this world, survival depended less on strength than on being right about the future.

Living inside uncertainty

Everything above explains how this pattern is visible in the archaeological record. What follows addresses what it meant to live inside it.

1. Which animals mattered — and why prediction mattered

The key animals in these systems were not small game or plants used daily. They were large, fat-rich mammals, especially:

- Aurochs (large wild cattle)

- Red deer

- Wild horses

These animals delivered:

- Dense calories

- Critical fat

- Large hides

- Bone and antler for tools

But they were not present year-round.

Their movements depended on:

- Snowpack retreat

- Spring grass emergence

- Passable river corridors

Humans could not control this. They could only predict it.

2. How we know people predicted in advance

Archaeology shows clear signs of anticipatory labor — work done before any animal arrived.

Across multiple sites and regions, we see:

- Toolkits with fresh resharpening immediately before kill layers

- Replacement of bindings and handles without evidence of breakage

- Sudden appearance of large butchery and hide-processing tools

- Camps reorganized for handling very large bodies

This is not opportunistic hunting. This is planned readiness.

The risk is obvious: If the prediction fails, the labor is wasted.

3. Absence is the signal — not presence

A critical point often missed in popular accounts: If these animals were available most of the year, their remains would appear scattered throughout occupation layers.

They do not.

Instead, archaeologists see:

- Dense clusters of remains in narrow horizons

- Followed by long stretches where those species disappear entirely

We know this absence is real because:

- People continue occupying the site

- Other animals continue appearing

- Tools continue to accumulate

The animals are missing because they were not there.

Waiting was unavoidable.

4. What happens when prediction is wrong

The archaeological record preserves stress, not emotion — but stress is readable.

In certain years and regions, we see:

- Fewer large animals taken

- More intensive bone breakage

- Higher rates of marrow and grease extraction

- Less selectivity in which bones are processed

- Greater reliance on secondary resources afterward

In plain terms:

People worked harder to get less.

These patterns increase toward the end of the Ice Age, when:

- Climate became more volatile

- Snow and grazing patterns shifted

- Migration routes became unreliable

This is not a failed hunt.

It is a failed expectation.

5. Why this mattered socially

When subsistence depends on brief events:

- Labor concentrates in short bursts

- Success or failure affects the entire year

- Knowledge becomes predictive rather than reactive

Children might see the key animal only once a year — or miss it entirely. Elders remember when prediction worked better.

Stories, in this context, are not myths.

They are forecasting tools.

6. This is not about animals — it is about risk

Everyone knows herds migrate.

What archaeology adds is this: prehistoric life often hinged on being right about the future — with no way to test the prediction except by waiting.

Waiting had costs.

Preparation had costs.

Being wrong had costs that lasted months.

This is the deeper pattern hidden beneath seasonal hunting.

Closing note

The opening scene is imagined.

The risk it describes is not.

Archaeology does not show us confidence.

It shows us commitment under uncertainty — sharpened tools, ready hands, and years when the valley stayed quiet longer than it should have. Risk in the Stone Age was not sudden — it accumulated quietly, season by season.

This blog exists to trace those moments —

one animal, one season, one valley at a time.