The evidence is literally in their teeth.

When researchers examined dental calculus—that mineralized plaque your dentist scrapes away—from human remains at Qesem Cave in Israel, they found something remarkable embedded in the 300,000 to 400,000-year-old tartar: microcharcoal. Tiny particles of smoke, inhaled so regularly over a lifetime that they became permanently trapped in the calcium deposits on ancient teeth.

These people weren’t occasionally warming themselves by a fire. They were living in smoke. Breathing it. Day after day, year after year, until it became part of their bodies.

Why would anyone do that?

The Invisible War

Imagine a summer evening 30,000 years ago in what is now southern Germany. The sun drops toward the horizon, the air cools, and from the marshes along the river, they rise. Mosquitoes. Clouds of them, homing in on the carbon dioxide you exhale, the heat your body radiates, the subtle chemical signatures of mammalian blood.

You can swat. You can run. Or you can do what humans learned to do somewhere in the deep past: you can sit in the smoke.

It seems counterintuitive. Smoke stings your eyes, irritates your throat, makes you cough. But the alternative—being fed upon all night by insects that leave you exhausted, infected, and maddened—is worse. Far worse.

And smoke, it turns out, is remarkably effective.

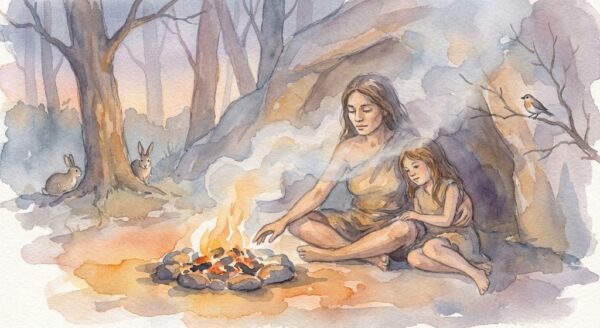

The Women at the Fire

Who tended these fires through the long nights? Who knew which wood smoked best, which position caught the breeze, which herbs to throw on the coals when the mosquitoes grew fierce?

In Stone Age communities—as in most traditional societies documented by ethnographers—fire-tending and camp maintenance fell largely to women. They were the ones who stayed closest to the hearth, who nursed children through the night, who would have suffered most from biting insects disrupting precious sleep. The knowledge of smoke wasn’t abstract. It was intimate, practical, and almost certainly passed from mother to daughter, from aunt to niece, from old woman to young.

When we imagine prehistoric life, we often picture men with spears. But the woman sitting in the smoke, eyes half-closed, feeding the fire with damp sage while her children finally slept—she was performing equally essential work. She was keeping her family alive.

The Science of Smoke

Mosquitoes find you primarily through carbon dioxide. You exhale; they detect the plume and fly upstream toward the source. It’s elegant, efficient, and millions of years old.

Smoke disrupts this system completely. The particulates scatter the CO2 gradient, making it impossible for mosquitoes to track. The rising heat creates air currents that small flying insects cannot navigate. The reduced oxygen near a fire makes the immediate area hostile to creatures that need to stay airborne. And many types of smoke contain compounds that are directly irritating or toxic to insects.

This isn’t folk wisdom. This is physics and chemistry, and our ancestors discovered it long before they could have explained it.

The Plants in the Smoke: 40,000 Years and Counting

Smoke alone drives insects back. But our ancestors discovered something more: certain plants, when burned, release compounds that mosquitoes find unbearable.

Wormwood. Mugwort. Juniper. Wild sage. These weren’t random choices. The aromatic plants of Stone Age Europe contain chemicals—thujone, camphor, terpenes—that don’t just smell strong to us. They’re actively toxic or repellent to insects. When a Stone Age woman threw a handful of mugwort on the fire, she wasn’t performing a ritual. She was deploying a fumigant.

This technology never died. Walk into any shop in India today and you’ll find the mosquito coils. That slow-burning green spiral is the same principle, refined: a wood-powder base that smolders like a tiny campfire, infused with pyrethrin from chrysanthemum flowers, often boosted with citronella, neem, or eucalyptus oils. Multiple plants, slow smoke, sustained release. The format was invented in 1890s Japan, but the formula is ancient: combine the right plants, burn them slow, breathe the smoke, survive the night.

Forty thousand years of innovation, and we’re still using the same solution. We just coiled it into a neater shape and printed a turtle on the box.

The Stone Age women who discovered which plants worked best—who tested, remembered, and taught this knowledge—were doing chemistry before chemistry had a name. Every mosquito coil lit tonight is their inheritance.

Even the battery-powered patio repellent devices on your neighbor’s patio—that sleek, smokeless device—runs on the same principle. Battery-powered heat vaporizes synthetic pyrethroids, descendants of chrysanthemum compounds. No smoke, no smell, same ancient chemistry. We’ve just learned to hide the fire.

What the Ethnography Tells Us

In Siberia, the Selkup people—reindeer herders living in one of the most mosquito-dense environments on Earth—observed something remarkable about their animals. The reindeer learned that human camps meant relief from biting insects. They would return to camp each evening specifically to stand in the smoke of the fires.

The Selkup responded by providing dedicated smoke fires for their herds—burning damp, smoky materials to create maximum insect-repelling effect. It became part of the daily rhythm: humans and animals gathered in shared protection against the swarms.

This isn’t a primitive stopgap. This is a sophisticated interspecies bargain, and it suggests how deep the smoke-as-medicine tradition runs.

The Burning of the Beds

At Sibudu Cave in South Africa, archaeologists found something that initially puzzled them. The site was occupied repeatedly over tens of thousands of years, with layer upon layer of carefully constructed bedding—sedges, leaves, and aromatic plants. But many of these bedding layers showed clear evidence of deliberate burning.

Why would you burn your own bed?

The answer, researchers now believe, is pest control. After weeks of occupation, bedding becomes infested with parasites—lice, fleas, mites, the accumulated hitchhikers of human habitation. Burning the bedding before leaving camp destroys these populations, leaving the site clean for the next occupation.

Fire wasn’t just keeping insects away during the night. It was sanitizing living spaces. Resetting the environment. Humans were managing their habitations 73,000 years ago with a sophistication we’re only now beginning to appreciate.

The Skill of Smoke

Here’s what’s easy to miss: using smoke effectively isn’t simple. It requires knowledge and skill.

You need to read the wind—position your fire so smoke drifts over the sleeping area without becoming unbearable. You need to manage the fuel—green wood and damp materials produce more smoke; dry wood produces more heat but less protection. You need to maintain the fire through the night, feeding it enough to keep smoking without letting it flare into a blaze that drives everyone back.

This is a technology. It’s invisible to us because it doesn’t leave stone tools or pottery shards, but it’s no less sophisticated than knapping a hand axe. And it required teaching. Someone had to show the children where to sit, how to arrange the fire, which materials to add for maximum smoke. The knowledge had to pass from generation to generation.

The smoke keeper was a role, even if we’ll never know what they called it.

Bringing the Forest Home

Modern insect control often starts with a chainsaw. Clear the brush. Remove the trees. Eliminate anything that might harbor pests. We treat our properties like fortresses under siege, and the enemy is anything green.

But think about what the research actually shows: our ancestors sought wind, not barrenness. They sought elevation, not deforestation. They used plants—aromatic, insecticidal, carefully chosen plants—not plant elimination.

A mature tree in your backyard isn’t a mosquito factory. It’s shade that cools your home. It’s airflow that disrupts insect flight. It’s habitat for birds that eat thousands of insects daily. It’s medicine, if you know how to use it—willow bark, pine resin, the aromatic compounds that our ancestors burned for protection.

When we tear out trees and pave over yards, we don’t escape nature. We just make it hostile. We create heat islands that breed mosquitoes in every forgotten puddle. We eliminate the birds and bats that would have helped us. We trade a living, working ecosystem for a dead zone that requires constant chemical intervention.

The Stone Age answer wasn’t “remove all nature.” It was “understand nature well enough to live within it.”

That understanding starts in your own backyard. Plant something. Let it grow. Learn what it does.

The Healers’ Inheritance

If you’ve read Jean Auel’s Clan of the Cave Bear or similar prehistoric fiction, you’ve met characters like Iza—women who carried botanical and medicinal knowledge that their communities depended upon. The smoke keepers were real versions of these women.

This wasn’t magic or mysticism. It was accumulated observation across generations. Which smoke repelled insects best? Which made you cough too much to sleep? Which kept the babies calm? These were life-and-death questions, and Stone Age women answered them through careful attention and memory.

The healer-woman of prehistoric fiction isn’t a romantic invention. She’s an echo of something real—women whose expertise in fire, smoke, plants, and survival made human life in a world of biting insects possible.

Living With the Smoke

That microcharcoal in ancient dental calculus tells us something important: our ancestors accepted the tradeoff. They knew smoke was unpleasant. They breathed it anyway, because the alternative was worse.

This is what living in a world of biting insects actually looked like. Not the romantic image of pristine wilderness, but a constant negotiation. Eyes watering, lungs adapting, bodies learning to tolerate one discomfort to avoid another.

When you next sit by a campfire and the smoke seems to follow you wherever you move, remember: you’re participating in the oldest medicine humans ever invented. Your ancestors sat in that same smoke, for the same reasons, across hundreds of thousands of years and every inhabited continent.

The fire was never just about warmth. It was about survival. And the smoke keepers—the ones who understood how to make it work—were as essential as any healer or hunter.

They just didn’t leave their tools behind for us to find.

The Backyard as Ecosystem

Here’s what strikes me most about our ancestors’ relationship with insects: they didn’t solve the problem by stripping the land bare.

They lived within forests, beside wetlands, among the plants and animals that shared their world. Yes, insects plagued them. But the answer was never to eliminate all vegetation, drain every pond, create a sterile perimeter of bare earth. The answer was knowledge—knowing which plants repelled insects, which trees created the right airflow, which landscapes balanced human comfort with ecological richness.

We’ve inherited a strange modern idea that nature belongs somewhere else. That a “nice” property means a clipped lawn, a few ornamental shrubs, and nothing that might harbor bugs or drop leaves. So we clear-cut our backyards and then drive an hour to walk through someone else’s forest, as if wildness were a destination rather than something that could live right outside our doors.

Our ancestors would find this baffling. The plants that protected them grew within arm’s reach. The smoke that saved them came from local wood. Their medicine cabinet was the landscape they inhabited.

What if we planted our yards like people who intended to live in them? A few trees for shade and airflow. Aromatic herbs that actually do something—yarrow, wormwood, mint. A landscape that works with the ecosystem instead of against it. Not a sterile buffer between us and nature, but a home within nature.

The Stone Age smoke keepers didn’t retreat from the living world. They learned its rhythms and used them. That knowledge is still available to us.

It starts with a single tree.