What fascinates me about Stone Age tools is not their crudeness, but their restraint. So little material. So few shapes. And yet, behind each object sits a chain of decisions we are still learning how to read.

Most of what we know about early Homo sapiens comes not from bones or shelters, but from stone—flakes struck in deliberate sequences, edges renewed again and again, tools carried, lost, remade. Even now, archaeologists regularly discover that tools once thought “simple” were part of complex systems of planning, repair, and teaching.

The Stone Age feels distant, yet its tools continue to unsettle us: they work too well, with too little, and they remind us how much knowledge can exist without writing, diagrams, or instruction manuals.

The moment

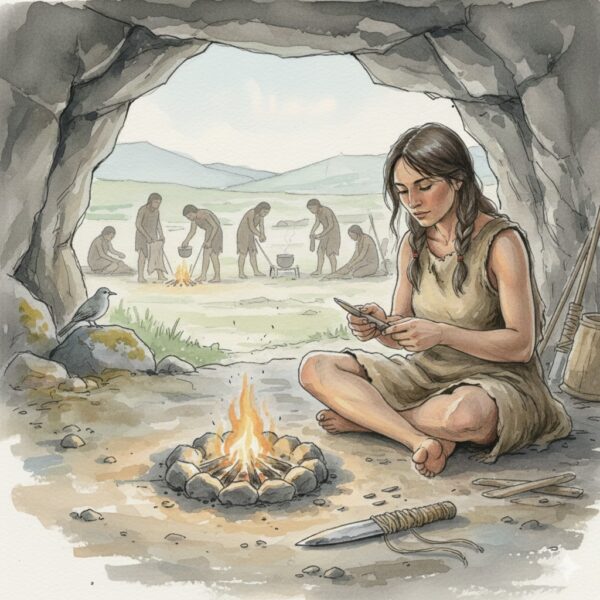

She did not make the tool today.

It had been made earlier, at another place, from stone carried a long way. What she did now was smaller. She sat near the fire and turned the edge toward the light, testing it with her thumb. A few strikes followed—controlled, practiced. Not to reshape the tool, only to wake it again.

The work was quiet. No one gathered to watch. When she finished, the edge caught differently. Sharper. Lighter. Ready.

Tools were not born in moments like this.

They were maintained.

She was not the one expected to leave camp that day.

Others would move out along the valley floor, following paths already walked many times that season. What she did instead happened close to the fire, where hands could work without interruption. Tools passed through her fingers one by one—tested, adjusted, returned. A handle loosened by damp weather was tightened. A binding worn thin was replaced. A blade dulled by yesterday’s work was brought back to life.

No one announced this labor, but everyone depended on it. A scraper that failed would slow hide processing. A weak edge would waste meat. A poorly hafted tool could injure the hand that used it. The success of the day’s work rested quietly on what happened here first.

By the time others left, the tools they carried already knew what they would be asked to do. Nothing about this work looked urgent. And yet, without it, nothing else would proceed smoothly. The camp did not move forward on effort alone. It moved on preparation.

Archaeological evidence

Stone tools dominate the archaeological record because stone endures. But what archaeologists study is not just the finished tool—it is the process frozen in debris.

At many Paleolithic sites, we find sequences of flakes that show learning rather than improvisation. Core preparation follows consistent patterns. Blades are struck at predictable angles. Retouch scars reveal repeated maintenance rather than one-time use. Some tools traveled long distances, carried across valleys and seasons, suggesting they were valued beyond immediate need.

Use-wear analysis shows edges dulled by plant processing, hide scraping, meat cutting, woodworking. The same tool was often repurposed many times. Breakage patterns reveal careful avoidance of waste. Even discarded tools frequently show signs of being exhausted rather than abandoned.

What survives is not just an object, but a decision trail.

Across Upper Paleolithic sites dating roughly 45,000 to 12,000 years ago, archaeologists repeatedly find evidence that tools were not made only at moments of need, but maintained systematically. Retouch flakes—small, regular chips removed to refresh cutting edges—often appear clustered near hearths rather than kill sites. This suggests resharpening took place in camp, before tools were carried out for use.

At several long-occupied sites in Ice Age Europe, stone tools show extensive use-wear followed by multiple episodes of edge renewal. Some blades were resharpened until their original shape disappeared entirely, becoming smaller, thicker, and more specialized with each cycle. These were not disposable objects. They were managed resources, kept functional for as long as stone would allow.

By the Late Paleolithic (approximately 20,000–12,000 years ago), toolkits often included items clearly designed for maintenance itself—retouchers, hammerstones, and anvils used not to create new tools, but to extend the life of existing ones. The archaeological record preserves these patterns as dense scatters of flakes and battered stones, showing that much of Stone Age technology happened not in dramatic moments, but in quiet repetition.

Impact — what tools meant in those times

Tools changed how people moved through uncertainty.

A sharp edge reduced effort. A reliable scraper extended the life of hides. A well-maintained blade shortened processing time when food arrived suddenly. Tools allowed work to be done faster, with less risk, and by fewer people—freeing others for gathering, care, or preparation.

But tools also structured knowledge. Knowing how to strike stone required observation and practice. Repair demanded memory: how this stone behaved, how far it could be pushed. Teaching happened through proximity, not explanation. Children learned by watching hands, not listening to rules.

In this way, tools were not just technology. They were memory made durable.

Closing

Stone Age tools appear simple because we no longer recognize the knowledge embedded in them.

What survives is stone. What is missing is the hand that shaped it, the judgment that stopped at the right moment, the understanding of when not to strike again. Tools remind us that much of human intelligence once lived outside language, preserved not in words, but in repeated acts.

We are still learning how to read that intelligence.