This post imagines a single human lifetime during the Ice Age—not to invent the past, but to make its slow changes visible. Archaeology tells us that cave bears vanished unevenly across Europe, cave by cave and valley by valley, while people were still living there.

What follows compresses those repeated disappearances into one remembered life, because extinction is not experienced as data. It is experienced as the last time something is noticed, and then never noticed again.

Every detail here stays within what evidence allows; what is imagined is only the point of view. The goal is not to recreate a scene, but to help the reader feel how loss enters a world quietly—long before anyone knows to call it extinction.

Prologue: What Lived in the Cave Before Us

Before wolves learned to fear humans, before mammoths became legends, before horses were hunted into flight, there was an animal so large it bent the ground where it slept.

The cave bear was not a bear that visited caves. It was a bear that lived in them.

For hundreds of thousands of years across western and central Europe, cave bears used the same limestone caves generation after generation. They were enormous—often larger than modern grizzlies—but mostly vegetarian, built for long winters, slow movement, and deep hibernation. Their bodies were shaped by caves: wide skulls, massive shoulders, thick bones that pressed shallow beds into cave floors.

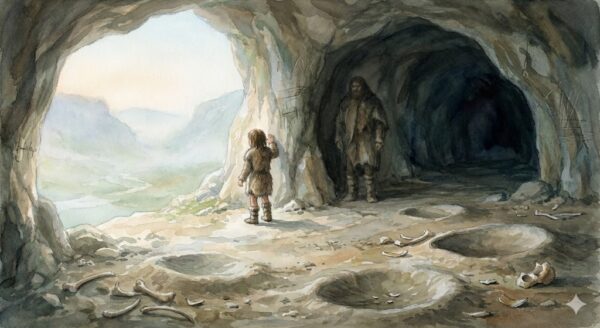

When humans arrived, they did not enter an empty landscape. They entered a world already claimed.

Caves were the best shelters Ice Age Europe offered. Dry. Protected. Predictable. Humans wanted them for the same reasons bears did. For tens of thousands of years, the two species shared these spaces—sometimes at different times of year, sometimes uneasily overlapping. Archaeology preserves this not as drama, but as layering: bear bones, then human ash, then bear again.

Then, around forty thousand years ago, the layering stopped.

Cave bears disappeared earlier than most Ice Age giants. Not everywhere at once, but fast enough that a single human could grow up hearing them and grow old never encountering one again. Climate pressure reduced their food. Humans increasingly occupied caves year-round. Cave bears, loyal to specific dens and unable to adapt quickly, fragmented and vanished.

Why should we care now?

Because this was the first time many humans learned what extinction felt like from the inside.

Not as catastrophe.

As silence.

What follows is not the story of the cave bear’s death.

It is the story of what happens to human memory when an animal vanishes slowly enough to be remembered—and long enough to be forgotten.

When This Happened

This story does not take place in the Copper Age, the Bronze Age, or any world with farming, villages, or metal.

It unfolds much earlier—during the Upper Paleolithic, roughly between 45,000 and 25,000 years ago, in western Europe.

There was no agriculture.

No pottery.

No permanent houses.

People lived by moving: following plants, animals, seasons, and weather. Tools were stone, bone, wood, sinew. Fire was carefully maintained. Caves were not symbolic spaces yet—they were shelter, claimed only when something larger did not already occupy them.

This was also a period of transition.

Neanderthals were disappearing. Modern humans were spreading. Ice sheets advanced and retreated. Landscapes changed within a single lifetime.

The cave bear vanished during this window.

Not in a mythic past beyond human memory—but early enough that no written culture ever described it, and late enough that living people could remember its presence.

This matters.

Because extinction here was not abstract. It was experienced personally—by people who grew up sharing space with the animal and grew old in a world where it no longer existed.

This is not prehistory as a blur.

It is history lived without writing.

The Last Time a Child Hears a Sound

Her earliest memory of the cave is not visual.

It is pressure.

Her father’s hand on her shoulder, firm but not afraid. A signal, not a warning.

She is four years old. The cave mouth exhales cool air, blue-shadowed even in summer. Water drips somewhere beyond sight. Her own breathing sounds too loud.

Then, beneath everything else, something moves.

Not a noise exactly. More like the cave itself is alive. A low, steady shifting that travels through stone instead of air. The ground seems heavier because of it.

“The bear sleeps,” her father whispers. “We do not wake it.”

She has never seen the bear. But she feels it. A presence above them, deeper inside, enormous enough to make stillness meaningful. The cave is not empty. It belongs to something else.

She learns this sound the way she learns the wind.

At six, she can tell whether the breathing is deep or restless.

At eight, she knows when to step lightly.

At ten, she stops being afraid and starts being attentive.

The bear becomes part of the valley’s language. Not a story. A condition.

Everyone listens before entering. Everyone knows which caves to avoid in certain seasons. Children are taught where not to run, where not to shout, where to wait.

Then one winter, the breathing does not return.

No one says anything at first. They listen longer. They wait. They come back another day.

The cave remains silent.

Gradual Absence

At twelve, she still pauses at the cave mouth. By habit, not fear.

At fifteen, she notices that adults enter without stopping. No listening. No tightening of shoulders.

The cave has become available.

This does not feel like loss. It feels like relief.

They gather ochre without hurry. They shelter deeper inside during storms. They leave tools behind overnight without concern.

The valley grows quieter in ways that are difficult to name. No more deep scrapes in clay. No fresh tracks wider than a man’s chest. No musky smell in spring.

The bear does not disappear. It thins.

In some valleys, people still hear it. In others, it becomes something spoken about elsewhere. “They still have bears beyond the ridge.” “In the high country.” “In the old caves.”

Then even those stories weaken.

By the time she is twenty-two, she enters the cave without listening.

This startles her later, when she realizes it.

She stands inside longer than necessary, aware of something wrong she cannot locate. The cave feels hollow, as if it has forgotten part of itself.

When her daughter is born three years later, she does not teach her to listen at cave entrances.

Not because she is certain the bear is gone.

Because she still half-expects the sound to return—and does not want her child to learn disappointment as a rule of the world.

This is how extinction enters a culture: not with mourning, but with adjusted teaching.

When the Animal Became a Story

Long after cave bears disappeared from the land, bears did not disappear from human imagination.

Across northern Eurasia, bears occupy a strange position in myth and folklore—not as ordinary animals, but as beings close to humans, sometimes ancestral, sometimes taboo, sometimes sacred.

In Slavic and Russian folklore, the bear is often unnamed directly, referred to by euphemisms meaning “the brown one” or “the master of the forest.” Scholars have long noted that this linguistic avoidance suggests an older fear or reverence—possibly inherited from a time when bears were larger, more dangerous, and more present in human living spaces.

In Finno-Ugric traditions, bears were treated as kin, guests, or former humans. Rituals surrounded their killing. Songs preserved their lineage. The animal existed half in the forest, half in social memory.

Farther east, Siberian cultures maintained elaborate bear ceremonialism, sometimes treating the bear as an ancestor whose spirit returned cyclically. These traditions emerged long after cave bears were gone, yet they preserved a sense of bears as more than wildlife.

Archaeology and ethnography together suggest a pattern:

When an animal disappears too early to be written about, but too late to be forgotten, it often survives as a boundary figure—part memory, part myth.

The cave bear likely entered this space.

Not remembered accurately.

But not erased either.

Stories carried its weight after the land no longer could.

When Stories Stop Matching the World

By middle age, the bear survives only in instruction.

“Don’t go too far back.”

“Caves belong to others.”

“They were dangerous once.”

Children repeat the words without context. They imagine a creature shaped like a modern bear, or a monster from exaggeration. The scale is wrong either way.

The land no longer confirms the stories.

No bones surface fresh from erosion. No claw marks deepen. No sounds return to correct imagination.

Elders speak with confidence. They remember weight. Smell. The way the ground felt different when the bear was near.

Younger listeners nod politely.

This mismatch is not conflict. It is drift.

Archaeology shows it too. Bear skulls placed deliberately in caves after bears are gone. Images scratched into stone long after living models have vanished. Ritual attention focused not on presence, but on memory.

The bear becomes something handled carefully in story because it no longer exists to contradict error.

This is the dangerous moment for truth: when the world stops enforcing accuracy.

Old Age Reflection

At sixty-seven, she realizes she can no longer remember the sound itself.

She remembers that it existed. She remembers how her body reacted to it. But when she tries to summon it, her mind offers substitutes: wind, water, breath.

They are wrong.

Her grandson asks her once what the bear was like.

She tries to explain. “The cave breathed,” she says.

He smiles, imagining something poetic.

“No,” she says. “It was alive.”

He nods again, kindly, still misunderstanding.

She does not correct him. How could she explain that the loss is not the animal?

It is the requirement to listen.

When she was young, the world demanded attention. Spaces were occupied. Silence meant danger, not safety. You could not enter everything simply because it was there.

Now the caves are empty, and anyone can take shelter without learning the old rules.

The world is easier.

And thinner.

She sits at the cave entrance longer than her grandson thinks necessary. Not listening for the sound. That habit died long ago.

But her body remembers what it meant to wait. To share space with something that did not care whether you lived or died.

When she dies, there is no one left who remembers the bear as anything other than a story.

The cave remains. The valley continues.

The animal no one saw again was not forgotten quickly.

It was remembered too long.

And then, finally, memory outlived its usefulness—and the world moved on without it.

Epilgoue

Archaeology has unearthed tens of thousands of cave bear remains across Europe—complete skeletons, skulls worn smooth by stone, and entire cave floors shaped by their bodies—making the cave bear one of the best-documented Ice Age mammals, not a mystery at all.

What Archaeology Knows About the Cave Bear

Cave bears (Ursus spelaeus) were often larger than modern brown bears, some standing over ten feet tall when upright, with massive shoulders and wide, blunt skulls built not for chasing prey but for processing tough plant foods. Isotope analysis of their bones shows they were mostly vegetarian, relying heavily on alpine plants, roots, and seasonal vegetation, which tied their survival closely to climate stability.

Unlike other bears, they did not merely shelter in caves—they returned to the same caves generation after generation, leaving behind deep “bear beds,” claw marks, and thick layers of bone that allow archaeologists to track their lives, deaths, and sudden absence with precision. We know when they lived, where they slept, what they ate, how fast they grew, and roughly when they disappeared—between forty and twenty-five thousand years ago, region by region—yet no written culture ever described them.

They vanished just early enough to escape history, and just late enough to be remembered by people who never learned how to write.

Why the Cave Bear Disappeared

The cave bear did not vanish because it was weak or poorly adapted; it disappeared because the world it was built for collapsed from two directions at once. Cave bears were larger than modern brown bears, but slower and calmer than grizzlies, shaped for long winters, predictable seasons, and reliable plant food.

As Ice Age climates grew colder and more erratic, the roots and alpine vegetation they depended on declined, shortening feeding seasons and making hibernation riskier. At the same time, humans increasingly occupied caves year-round, using the very shelters cave bears relied on to survive winter. Unlike other bears, cave bears showed strong loyalty to familiar dens and were slow to relocate or change behavior. This combination—shrinking food outside and growing competition inside—proved fatal.

Between about forty and twenty-five thousand years ago, cave bear populations collapsed region by region, not everywhere at once, until the animal disappeared entirely: too early to be written about, and too late to be forgotten by the people who had once shared their caves.