What keeps me working in the Stone Age is not mystery, but competence. The deeper I go into archaeological material—especially when writing healer-women stories—the harder it becomes to believe that people lived by improvisation or instinct alone. They didn’t. They lived by remembering what had worked before, in worlds where nothing was guaranteed to work again.

What fascinates me is that this memory did not live in stories, symbols, or records. It lived in places that were tested and retested: hearths rebuilt, paths reused, tools repaired, bodies cared for long enough to recover. These were not traditions preserved for their own sake. They were practical answers to a single question repeated year after year: does this still work?

This post explores how memory functioned before writing—not as narrative, but as return under risk.

The moment

The people had come from far to this new and yet strangely familiar place. The woman knew they would be hungry when they woke.

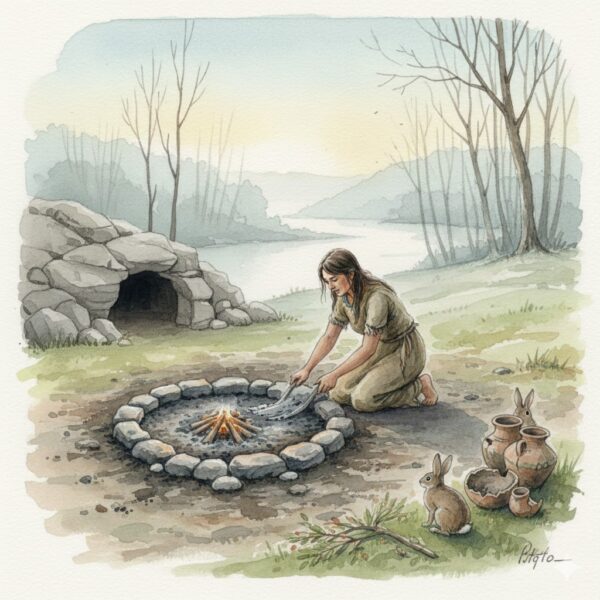

She comes back to the hearth before the others wake.

The ash is cold. That is expected. She scrapes it aside carefully, exposing the darker earth beneath. The circle is still there—flattened, compacted by years of fires built and rebuilt in the same place. She knows how deep she can dig before hitting stone. She knows where smoke will drift once the fire is lit. She knows which direction the wind usually comes from at this time of year.

None of this is written. None of it is spoken.

She rebuilds the fire where it has always been rebuilt, not because she believes it will work, but because this is how she will find out whether it still does. If smoke stalls. If fuel burns too fast. If heat escapes instead of holding. The hearth is a mark that promises predictability.

By the time others arrive, the fire is already answering.

The hearth returns

If there is one image to hold onto from this post, it is this:

A hearth rebuilt in the same spot, year after year, even though no one knows whether the valley will cooperate again.

This is not nostalgia.

It is not ritual.

It is not comfort.

It is memory functioning as risk management.

Across large parts of Europe, Asia, and the Near East, archaeological sites dating from roughly 300,000 BCE through 12,000 BCE show repeated fire use in nearly identical locations. Ash layers stack vertically. Burnt earth compacts. Stone debris clusters in the same arcs around fire pits.

This repetition is too precise to be accidental.

People remembered where fire worked best—and returned to find out if it still would.

Everything else in this essay orbits that fact.

Marks of Fire → Memory of Reliability

The mark: Rebuilt hearths in the same location.

The memory: Knowing where fire behaves predictably.

What archaeology shows

In Middle and Upper Paleolithic sites, hearths are often reconstructed in nearly the same position across multiple occupations. This pattern appears in caves, rock shelters, and open-air camps dated from ~200,000 BCE onward, intensifying after ~50,000 BCE with more frequent and structured fire use.

The ground itself records this memory. Repeated heating alters soil chemistry. Ash lenses accumulate. The space becomes legible to those who return.

What this meant

Fire is not neutral. In the wrong place it smokes, wastes fuel, blinds eyes, and leaks heat. Remembering where fire works reduces risk every single night.

Returning to the same hearth location is not habit.

It is an informed gamble.

If it fails, the place fails.

Worn Paths → Memory of Movement

The mark: Compacted ground and repeated movement corridors.

The memory: Knowing which routes are worth taking again.

What archaeology shows

Across river valleys such as the Danube, Dordogne, and Rhine systems, site clusters from ~40,000–12,000 BCE align along predictable movement routes. These are not random scatterings. They form chains of use: river crossings, sheltered bends, reliable approaches.

Repeated foot traffic leaves subtle but measurable changes in sediment density and wear. Camps appear where movement slows. Refuse accumulates where people pause.

What this meant

Movement itself carried memory.

Returning along known routes did not mean safety. Rivers flooded. Snowpack shifted. Valleys could fail. But unknown routes carried unmeasured risk.

Returning allowed comparison.

If a path no longer worked, people learned that quickly.

If it still did, the knowledge deepened.

Tool Retouch → Memory of Materials

The mark: Retouch scars and exhausted tools.

The memory: Knowing which tools are worth repairing.

What archaeology shows

From roughly 70,000 BCE onward, stone tools show extensive maintenance. Edges are refreshed again and again. Tools shrink predictably through use. Retouch flakes cluster near hearths, not kill sites, indicating preparation before work begins.

Some tools are carried long distances, suggesting remembered value rather than convenience.

What this meant

Stone is not equal.

Some fractures cleanly. Some shatter. Some hold edges through repeated renewal. Remembering which stones were worth keeping reduced waste and effort.

Tools were not made once.

They were remembered through repair.

The body as a remembered site

Marks and memory did not stop at land and stone. They extended into bodies.

Healed fractures, joint degeneration, tooth loss followed by continued survival—these appear throughout Paleolithic skeletal remains. Healing takes weeks or months. Survival through impairment requires adjustment.

The body itself became a record.

Memory here meant knowing how long healing takes, when movement can resume, when it cannot. These timelines are not intuitive. They are learned through repetition and loss.

Care was not symbolic.

It was remembered outcome.

Portable memory

By the time we reach the late Neolithic and early Copper Age, around 3300 BCE, we see memory carried on the body itself.

The belongings of Otzi the Iceman include not general supplies, but tested ones: fire-starting materials, medicinal fungi, retouched tools, repair items.

This is memory made portable.

Not “what might be useful,” but what has worked before.

Why writing changes everything

Writing does not invent memory.

It changes where memory lives.

Before writing, memory is embedded in: places that are revisited, tools that are repaired, bodies that recover, paths that are worn.

After writing, memory can be detached from place. Stored. Transported without return.

This is a profound shift—but it builds on something older.

Writing replaces land-based memory with record-based memory.

It does not erase the need to test reality again.

Why women appear at the center of this

The kinds of memory archaeology allows us to see—maintenance, return, care, preparation—align with forms of labor historically carried out close to camp.

These activities leave fewer dramatic traces than hunting or construction. But they structure survival.

The hearth rebuilt.

The tool repaired.

The body kept alive long enough to heal.

Memory here is not heroic.

It is cumulative.

Closing — the thing to remember

If a place was remembered, it deepened.

If it was forgotten, it disappeared.

Stone Age people returned to the same places not because they trusted them, but because return was the only way to learn whether the world would cooperate again.

The hearth was not a symbol of home.

It was a question asked year after year.

And the land answered.