Prehistory did not survive on violence. It survived on women who didn’t sleep.

The most dangerous moment in the Stone Age was not the hunt.

It was the long stretch before dawn—when the fire weakened, the cold pressed in, and everyone else was unconscious.

If the fire failed, people didn’t suffer heroically.

They froze. Quietly. In their sleep.

This is not a metaphor. It is written in the archaeological record: hearths kept alive night after night, ash layered patiently in the same place for generations. Fire was not made casually. It was preserved. Guarded. Watched.

Someone had to stay awake.

And it was rarely the hunters.

While history celebrates weapons and kills, archaeology tells a different story—one centered on domestic survival, vigilance, and care. The labor that kept children breathing, the sick warm, and communities alive left no monuments. It left ash.

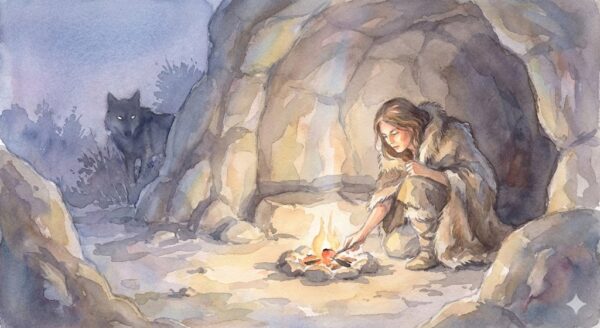

This story begins where human history was actually decided: at the fire, before dawn, in the hands of women history forgot to name.

The Predator Before Dawn

A Stone Age story based on archaeology, about the night fire died—and the woman who refused to sleep.

The fire died in the hour before first light.

It didn’t collapse in sparks or explode in drama. It simply stopped breathing.

One moment there was a low, red pulse at the center of the prehistoric hearth. The next, only a dull smear of gray ash—no glow, no warmth rising to the skin. Just silence.

In the Ice Age, this wasn’t an inconvenience. It wasn’t a mistake.

It was a countdown.

Outside the circle of dying light, the cold waited. Not like weather. Like a living thing. It pressed inward from the dark, heavy and patient, a predator as old as memory that knew exactly what to do when the fire failed.

It didn’t rush. It never rushed.

It crept.

She felt it first in her feet. Then in her spine.

She was already awake.

In Stone Age daily life, someone always was.

The others slept in a tight ring—hunters sprawled in exhaustion, children bundled together like littermates, the old breathing shallow and uneven. Fur cloaks rose and fell. No one stirred.

She was the only thing standing between them and the dark.

This was prehistoric survival at night: not running, not fighting, but refusing to lie down when every muscle begged for it.

Her eyes burned from smoke and fatigue. She had been awake since dusk, feeding the fire slowly, carefully. Not too much wood—never too much. Damp fuel meant smoke, and smoke carried scent. Scent carried attention.

And attention, out here, meant teeth.

She leaned forward, close enough that the ash warmed her cheeks, and peered into the pit.

Nothing.

Her stomach tightened.

She did the math the way women always had, long before numbers had names.

If the ember had gone fully black, there would be no flame before dawn.

If the tinder was damp, it would smother instead of catching.

If the fire failed completely, there was no second chance.

No sparks in the dark.

No flint to waste.

No “later.”

This was fire keeping in prehistoric times—a job without forgiveness.

The cold pushed closer. She could feel it now, crawling along the ground, seeping into the furs. A child whimpered in sleep and turned toward the hearth, seeking warmth that was no longer there.

She heard something beyond the light.

Not wind.

A sound too deliberate for that.

A snap.

Her breath caught. Her heart slammed against her ribs, loud enough that she feared it would wake the camp—or worse, announce her to whatever moved out there. She didn’t reach for a spear. A spear would be useless if the fire didn’t return.

This wasn’t a hunt.

This was an invisible war.

She crouched lower and stared into the ash. For a long moment, she saw nothing. Then—barely—a pinprick of orange.

One eye.

Alive.

She leaned closer, ignoring the sting of heat against her face. This part required care. Too hard a breath would scatter ash and kill the ember. Too soft, and it would starve.

She didn’t blow.

She breathed.

Slow. Measured. Controlled. She fed the ember her own life, a thin stream of air drawn from deep in her chest. The ember brightened, then faltered.

The cold seemed to lean in, sensing weakness.

She breathed again.

The ember dimmed.

Her jaw tightened. She could hear it now—the weight in the dark shifting, testing the edge of the light. The cold was not alone. It never was.

She reached inside her tunic and closed her fingers around the last thing she hadn’t used.

The emergency stash.

Dried moss, kept warm against her skin all night. She had carried it since autumn, replacing it carefully, never touching it unless the fire truly faltered. This was not fuel. This was a promise.

She laid it gently over the ember.

For a heartbeat, nothing happened.

Then the ember bit.

A thin thread of blue smoke curled upward, fragile as breath in winter air. She held herself perfectly still. One careless movement could scatter everything.

The smoke thickened.

A spark leapt.

Then—fire.

Not a blaze. Not yet. Just a thin tongue of gold licking upward, pushing back the gray. Light spread across the hearth stones. Shadows retreated.

Whatever had been moving beyond the firelight stopped.

Then withdrew.

The cold recoiled, wounded but not gone.

She fed the flame slowly, building it back the way women always had—layer by layer, patience over force. This was ancient fire tending, passed hand to hand, mother to daughter, elder to apprentice, without ceremony or record.

Fire was not a tool to her.

It was a living thing that remembered who cared for it.

Across the world, long before this camp and long after it would be dust, people would understand fire the same way. In the far north, hearths were spoken to gently, as if they could hear. In frozen forests, neglecting the fire meant sickness. In ancient households, the domestic flame—kept by women—marked continuity itself. In the high mountains, fire stayed alive for ancestors, not gods.

Fire watches back.

Fire remembers who stayed awake.

She sat until dawn, muscles trembling, eyes stinging, listening to the fire’s breath return to something steady. When the sky finally lightened, she allowed herself to lean back against the stone.

When the camp stirred later, the lead hunter stretched, cursed the cold, and reached for his spear. He glanced at the hearth and frowned.

“Fire’s getting low,” he muttered.

She didn’t answer.

He had no idea that, in the darkest watch before dawn, he had almost died in his sleep.

He didn’t need to know.

This is the quiet truth of women in the Stone Age. They were not standing behind history. They were holding it together through nights like this—through vigilance, restraint, and refusal to close their eyes.

When you look at a prehistoric hearth in a museum, you are not looking at a cooking site.

You are looking at a battlefield.

And if you are here to read this—warm, alive, breathing—it is because, long before clocks and names for hours, someone stayed awake in the last dark stretch before morning and would not let the fire die.

Epilogue

This story was not imagined first and justified later.

It emerged from archaeological patterns: persistent hearths, repeated ash deposits, and living spaces organized around fire rather than weapons.

Ethnographic research shows that in societies without easy fire-starting technology, fire maintenance—especially overnight—fell to those who remained in camp caring for children, the sick, and the elderly.

Once this evidence is taken seriously, the story becomes unavoidable.

The question is no longer whether someone stayed awake.

It’s why we stopped noticing them.

Myth-busting Stereotypes about Stone Age Women

History calls the Stone Age violent. Archaeology calls it domestic.

We were taught that prehistory was shaped by hunters, weapons, and kills.

But the archaeological record tells a quieter, more unsettling story.

Survival did not hinge on who struck hardest. It hinged on who stayed awake when everyone else could sleep.

That work did not leave trophies.

It left ash.

The following explainer contrasts long-standing assumptions about Stone Age life with what archaeology, spatial analysis, and ethnographic comparison actually indicate. The “Before” side reflects interpretations shaped by what preserves best in the archaeological record—tools, weapons, and dramatic events. The “After” side focuses on quieter but more reliable signals: repeated patterns, living-space organization, and cross-cultural evidence that reveal how survival was sustained day after day.

A quick “what we assumed” vs “what the evidence suggests” snapshot.

What We Were Taught

Old AssumptionWhy It PersistedMen were the primary actorsHunting leaves dramatic toolsFire was mainly for cookingHearths misread as utility sitesWomen’s work was secondaryDomestic labor doesn’t fossilize

What Archaeology Actually Shows

Archaeological EvidenceWhat It ImpliesPersistent hearths with layered ashFire was maintained continuouslyHearths centered in living spacesFire structured daily lifeEthnographic parallels worldwideFire tending fell to those who stayed in camp—often women or elders

Fire, Survival, and the Prehistoric Hearth: What Archaeology Reveals About Women in the Stone Age

Persistent hearths, ash layers, and ethnographic parallels reveal who stayed awake before dawn—and why it mattered.

Archaeologists don’t usually excavate “women” or “men.” They excavate patterns—and one of the strongest patterns in Paleolithic sites is the hearth. Not a dramatic bonfire, but a modest, repeatedly rebuilt fire spot layered with ash, charcoal, cracked stones, and food residue. These hearths sit in the same place over months or years, suggesting not chaos but routine.

What’s interesting is when hearth maintenance mattered most. Fire rarely went out during the busy daylight hours. The danger window was the cold, quiet stretch before dawn, when embers dimmed and everyone else slept. Ethnographic studies of recent hunter-gatherer societies show that this low-activity, high-risk task—tending embers, feeding just enough fuel—was typically done by those staying near camp rather than those ranging far.

A fun fact often overlooked: starting fire from scratch wasn’t just difficult—it was risky. Spark stones and friction methods worked, but slowly and unreliably, especially in damp conditions. Letting a fire die meant losing warmth, cooked food, hardened tools, and protection from predators in one stroke. The archaeological record doesn’t name the fire-keeper—but the continuity of domestic space strongly hints at who carried that responsibility.

Hunters came and went. The hearth stayed. Yet history remembered the spear and forgot the hands that kept the fire alive.

The Women Who Kept Humanity Alive While History Slept

Why prehistoric women’s daily labor—revealed by archaeology—has been erased from our understanding of the Stone Age.

For a long time, Stone Age history was told through what left the biggest marks: spears, bones, dramatic hunts. Daily work—especially work done close to camp—was treated as background noise. Feminist archaeology flips the lens and asks a sharper question: What if survival depended more on continuity than conquest?

Grinding plants, preparing hides, monitoring children, treating injuries, managing food stores, keeping fire alive—these tasks rarely fossilize as heroic artifacts. Yet they show up indirectly everywhere: in worn grinding stones, in repetitive hearth rebuilding, in plant residues, in healed fractures that suggest long-term care.

Here’s a curious twist: skeletal evidence increasingly shows women in prehistory had strong upper bodies and repetitive-strain markers—hardly the passive figures of old textbooks. The “invisible” work was physically demanding and cognitively complex. Knowing when to add fuel, how to bank embers, or which plants soothed burns wasn’t instinct—it was learned expertise.

History didn’t forget these women because they did nothing. It forgot them because they did everything that left no monuments.

Fire was not just heat. It was protection for sleeping children, the sick, and the old—maintained through nights when everyone else could afford to rest.

The most dangerous hour wasn’t the hunt. It was the moment just before the sky lightened—when dreams ran deep, muscles slackened, and the fire shrank to a red eye under ash.

Someone always stirred then.

Archaeology can’t tell us her name, but it tells us the setting: a ring of stones, a bed of coals, a careful hand that knew the difference between smothering a fire and feeding it. Too much wood wasted precious fuel. Too little, and the fire slipped away.

Fun fact: embers can stay alive for hours if treated correctly. The skill isn’t dramatic—it’s patient. That patience is written into the soil layers archaeologists uncover today.

Long before stories were carved or written, survival depended on this quiet refusal to sleep. The fire lived because someone chose to wake.

When archaeologists find ash layered again and again in the same place, they are not finding a cooking site. They are finding proof that someone stayed awake.

The Stone Age didn’t survive on strength alone. It survived on vigilance—the kind that leaves no monument, only ash.

If the Fire Died, Everyone Died

Why the most dangerous moment in the Stone Age wasn’t the hunt—but the hour before dawn.

We love to imagine prehistoric danger as sudden and violent. In reality, the greatest threat was boring, cold, and slow.

If the fire went out, there was no backup plan. No matches. No easy restart. Fire meant cooked food (safer calories), warmth, light, hardened tools, predator deterrence, and social cohesion. Lose it, and a group could spiral fast—especially in winter.

Here’s the counter-intuitive part: firekeeping wasn’t about strength. It was about attention. The skill lay in knowing embers—how they breathe, how they hide heat, how they lie to you just before they fail.

So the Stone Age’s most lethal moment wasn’t a charging animal. It was silence, cold ash, and the realization—too late—that no one had stayed awake.

What We Learn from Archaeology and Science about Stone Age Women

Long before fire was something that could be made at will, it was something that had to be kept.

Across the prehistoric world, archaeologists have found not the traces of casual flames, but of persistent hearths—fires that were maintained, preserved, and returned to again and again. These were not accidental burn marks or short-lived cooking fires. They were stable centers of life.

At one of the sites in middle-east, dating to nearly 790,000 years ago, excavations revealed repeated concentrations of burned flint microartifacts clustered in specific areas. The spatial patterning is precise: burned materials appear consistently in the same locations over long periods, surrounded by unburned zones. This is not what a natural wildfire leaves behind. It is the signature of a maintained hearth—fire preserved and controlled, not recreated from scratch each day.

In Kebara Cave, hearths appear embedded within structured living spaces. Ash layers accumulate in place, one atop another, indicating repeated use over time. The hearths are positioned where people slept, worked, and tended to the vulnerable—not near cave entrances or hunting preparation zones. Fire here was domestic, not opportunistic.

Far to the north, at Dolni Vestonice, hearths are associated with dwellings and long-term habitation. Thick ash deposits, charcoal lenses, and burned clay show that fire was central to daily life. These hearths were not moved. The camp organized itself around them.

From these findings, one conclusion becomes unavoidable: fire was someone’s responsibility.

Fire in the Stone Age was not primarily a hunting tool. It was not just for roasting meat or hardening spear points. It was heat in freezing nights, light in predator-filled darkness, protection for the sick and the very young, and a way to make food safe enough to eat. Hunters came and went. The hearth stayed.

Ethnographic parallels from later traditional societies reinforce this pattern. Across diverse cultures—Arctic, subarctic, pastoral, foraging—the maintenance of the domestic fire, especially overnight, most often fell to women or elders. This was not a matter of ideology. It was a matter of logistics.

Those who remained in camp—those caring for children, the injured, and the old—were the ones positioned to notice the fire’s needs. A hearth left untended could die quietly, without drama, long before dawn. Rekindling fire without reliable ignition tools was difficult, sometimes impossible. The cost of failure was not inconvenience, but exposure, illness, and death.

The archaeological record does not preserve names. It does not preserve voices. But it preserves patterns: ash laid down slowly, deliberately; fire returned to night after night; living spaces built around heat and light.

From this, we can say with confidence that someone stayed awake when others slept. Someone watched the fire breathe. Someone fed it just enough to keep it alive.

Our story in this post is an imagining of one such night—not as fantasy, but as the most likely human reality suggested by the ground beneath our feet.

When historians called this “primitive life,” they weren’t describing a lack of intelligence.

They were describing whose intelligence they didn’t bother to see.