Many of us think that care-giving is a modern age idea. However some Stone Age individuals survived injuries that would have prevented walking or hunting, leaving behind skeletons that record months or years of care rather than sudden recovery.

In this post, I move between brief imagined moments and the archaeological record to understand how early Homo sapiens lived with injury, care, and time—how survival depended not only on strength or skill, but on patience, memory, and the willingness to stay with one another when outcomes were unclear.

The moment

The injury was not new.

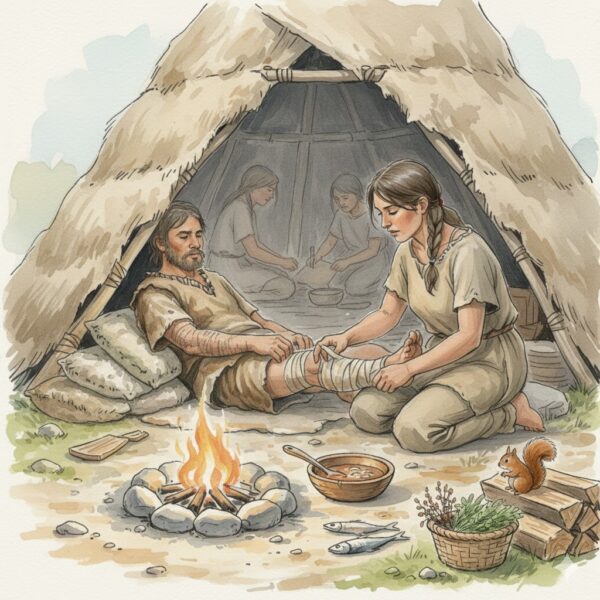

The bleeding had stopped days ago. The swelling had gone down enough that the skin no longer shone. But the leg still could not carry weight. When she shifted him, he clenched his jaw without sound. The fire was kept low. Water was warmed, not boiled. The wrap was loosened, cleaned, replaced.

There was no question of when he would walk again. That answer did not exist yet.

What mattered was that he was still alive this morning, and that he would be alive tonight. Someone brought food. Someone else took his place on the path they usually walked together. Time moved differently now, measured not in distance or return, but in whether pain eased or worsened.

This was not a moment of rescue.

It was a stretch of days.

Foundational archaeological perspective

In deep prehistory, injury is common. Healing is not.

The archaeological record preserves broken bones, crushed joints, damaged teeth, and degenerative changes in skeletons across the Paleolithic. What matters is not that injuries occurred—they inevitably did—but that many individuals survived long after injury, often for months or years.

Fractures show clear signs of remodeling. Bone ends knit together. Surfaces smooth. In some cases, healing is incomplete but advanced enough to demonstrate prolonged survival. Joint degeneration indicates years of altered movement. Tooth loss without corresponding malnutrition suggests continued feeding despite impaired chewing.

These are not instantaneous recoveries. They are timelines.

Healing leaves a signature that cannot be rushed. It requires immobilization, protection, nourishment, and above all, time. In a mobile foraging society, time is the most expensive resource there is.

Reading survival in injured bodies

Archaeologists do not assume care simply because a bone healed. They ask what survival would have required.

Some injuries prevent effective walking. Others limit arm strength, grip, or balance. Still others impair vision or cause chronic pain. When these injuries heal partially or fully, it implies that the injured person was not forced to keep pace, hunt, or forage at full capacity.

Survival under these conditions requires accommodation.

Someone else must carry food. Movement must slow or reroute. Camps must be chosen with accessibility in mind. Tasks must be redistributed. The injured body becomes a constraint on the group’s rhythm.

This is not sentiment. It is logistics.

Healing converts individual injury into collective cost.

How do we know this was care?

The clearest evidence for care is time passing under protection.

Bone healing follows predictable biological stages. In fractures, callus formation appears within weeks. Remodeling takes months. Full functional recovery may take much longer—or never occur at all. When skeletons show advanced healing of injuries that would have prevented independent survival, the conclusion is unavoidable: the individual was supported during recovery.

In some cases, survival extends beyond healing. Degenerative changes indicate years of altered movement. Repeated stress markers show compensation rather than collapse. Tooth loss without signs of starvation indicates continued access to prepared food.

These patterns cannot be explained by luck. They require sustained attention.

Importantly, the archaeological record does not preserve how care was provided—only that it was. We infer care not from tools or structures, but from outcomes that could not occur without it.

Injury as a long problem

Injury in deep time was not an event. It was a condition.

A broken leg did not mean a pause. It meant a reorganization of life. Hunting strategies shifted. Gathering routes changed. Risk increased for everyone. A group slowed became more vulnerable to predators, to scarcity, to missed seasonal windows.

Choosing to keep an injured person alive meant accepting those risks.

This reframes care entirely. It was not an instinctive reaction to crisis. It was a commitment sustained over time, often without certainty of success.

Some individuals recovered and returned to activity. Others lived with permanent impairment. In both cases, survival required ongoing adaptation by the group.

Care did not end when bleeding stopped.

Living inside dependency

Dependency alters social structure.

An injured person cannot reciprocate immediately. They consume without contributing in visible ways. In a subsistence economy, this is not trivial. It demands trust—not in character, but in continuity.

Care also demands knowledge. Wounds must be cleaned. Swelling managed. Movement restricted without causing further harm. Food must be prepared in forms the injured can consume. These tasks require experience and judgment.

This labor leaves little archaeological trace. There are no tools that say “care.” No features that mark patience. What remains is survival where survival should not have been possible.

In this way, dependency becomes visible only in hindsight.

What this meant in those times

Care reshaped survival.

Groups that sustained injured members accumulated knowledge about healing timelines, pain management, and recovery. They learned what injuries were survivable and which were not. They learned how long to wait.

This knowledge did not exist as theory. It existed as memory. Someone remembered that swelling eased after days, not hours. That movement too soon worsened outcomes. That certain plants soothed pain or reduced infection. That warmth mattered. That rest mattered.

Over time, care became part of how risk was calculated.

Survival was no longer only about strength or speed. It was about whether a group could absorb loss of function without collapse.

Care as infrastructure

In modern contexts, care is often framed as moral. In deep time, it was infrastructural.

It required:

- Food redistribution

- Task reassignment

- Altered movement patterns

- Patience under risk

- Knowledge transmitted across generations

This infrastructure did not build monuments. It did not accumulate wealth. It left no record of intention.

But it allowed people to survive injuries that would otherwise have been fatal.

It allowed knowledge holders to age. It allowed children to grow after illness. It allowed experience to accumulate rather than reset with each loss.

Care lengthened lives. Longer lives changed everything.

Illness, weakness, and gradual decline in stone age

Illness rarely leaves clean traces in the archaeological record. Unlike fractures, sickness often passes without marking bone at all. Yet prolonged survival through weakness, infection, or gradual decline can still be inferred through patterns of endurance rather than recovery. Individuals show signs of nutritional stress followed by stabilization, repeated episodes of illness rather than sudden death, and age-related degeneration that implies continued support as strength diminished over time.

Living with illness required a different kind of care than injury. There was no visible wound to bind, no clear moment of improvement to wait for. Weakness unfolded slowly. Appetite faded. Movement shortened. The work of care became quieter and more constant—adjusting food, reducing exertion, accommodating unpredictability. Survival depended less on intervention than on persistence.

Gradual decline reshaped the meaning of usefulness. Those who could no longer hunt or travel far still carried memory—of seasons, places, remedies, and past outcomes. Keeping them alive preserved more than a body; it preserved accumulated knowledge. In this way, illness did not only test compassion or endurance. It tested whether a group valued continuity over efficiency, and whether survival could include those who no longer moved at full strength.

Closing note

Survival before certainty did not always look like endurance or force.

Sometimes it looked like waiting.

Sometimes it looked like slowing down.

Sometimes it looked like staying with someone whose future was unclear.

The archaeological record does not preserve compassion.

It preserves time.

And time tells us this: people were kept alive when they could not have survived alone.

That choice reshaped what it meant to live at all.